Pierre L’Enfant. De Sibour is best remembered

for the private mansions he designed up and

down Massachusetts Avenue on Embassy Row,

which are now residences, chanceries

and embassies of Canada, Columbia,

France, Luxembourg, Peru, Portugal,

Spain and Uzbekistan. These buildings

reflect de Sibour’s genius as a master

synthesizer of the French Beaux Arts

style and American tastes of the time.

It is ironic that de Sibour became

an architect by accident. He didn’t

know what he wanted to do after he

graduated from Yale, so his architect

brother Louis got him a job at a

prestigious design firm in New York.

De Sibour was not happy there and probably

would have left the profession, had it not

been for the renowned architect Bruce Price,

who became his mentor. De Sibour joined

Price’s firm, then took his boss’s advice and

went to Paris to study at the same school

Louis had attended, the world-famous Ecole

des Beaux Arts.

De Sibour practiced in New York, then

married and moved to Washington in 1909,

where he already had a following. He was

handsome, charming, gregarious and made

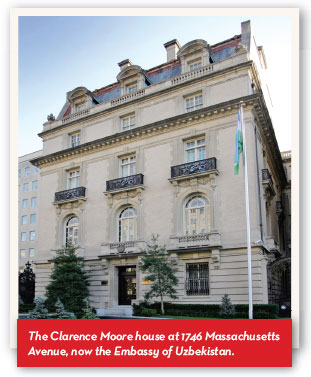

friends easily. He became a friend of Clarence

Moore, a coal magnate, who was master of the

hunt at the Chevy Chase Club. De Sibour

designed the clubhouse at Chevy Chase and

Moore’s own magnificent residence. The Beaux

Arts gem at |

In the early 1900s, Dupont Circle rivaled

New York’s upper Fifth Avenue as the

place for prominent and wealthy people

to congregate, and it was the first time

Washington had a concentration of people rich

enough to define themselves by the homes they

built. The captains of industry and commerce were

as wealthy as kings and commissioned houses

as grand as European palaces. Many of them

found the appropriate symbol for their status in

the exuberant Beaux Arts style, and the perfect

architect in Jules Henri de Sibour.

De Sibour had credentials that impressed

his American audience: his mother was from

Maine and his father, Vicomte Gabriel de Sibour,

was a direct descendent of French King Louis

IX. In the 30 years Jules de Sibour worked in

Washington, he produced a staggering number

of private homes, theaters, hotels and office

buildings, from the Folger Library to the Jefferson

Hotel. His elegant McCormick Apartment

Building, which now houses the National Trust

for Historic Preservation, shows the masterful

way he accommodated the Beaux Arts style to

the angular lots of the city’s complicated grid,

which was laid out by an earlier French visionary,

Pierre L’Enfant. De Sibour is best remembered

for the private mansions he designed up and

down Massachusetts Avenue on Embassy Row,

which are now residences, chanceries

and embassies of Canada, Columbia,

France, Luxembourg, Peru, Portugal,

Spain and Uzbekistan. These buildings

reflect de Sibour’s genius as a master

synthesizer of the French Beaux Arts

style and American tastes of the time.

It is ironic that de Sibour became

an architect by accident. He didn’t

know what he wanted to do after he

graduated from Yale, so his architect

brother Louis got him a job at a

prestigious design firm in New York.

De Sibour was not happy there and probably

would have left the profession, had it not

been for the renowned architect Bruce Price,

who became his mentor. De Sibour joined

Price’s firm, then took his boss’s advice and

went to Paris to study at the same school

Louis had attended, the world-famous Ecole

des Beaux Arts.

|

1746 Massachusetts Avenue was

called “one of the finest houses ever erected

in the city” by the AIA Guide to Washington

Architecture. Unfortunately, Moore was never

able to enjoy his new home, because he took

a trip to England to purchase hunting dogs for

the club and booked his return passage on the

one and only voyage of the Titanic.

During the Great Depression, many of

the fine homes were closed up. Few people

who lived in Washington needed ballrooms or

an entire separate floor for servant’s quarters.

Luckily for us, these grand houses were not

torn down, since they were ideally suited as

embassies, consulates and public buildings, and

that’s what they are today.

Thomas Jefferson once predicted that

fine architecture would improve the taste of

his countrymen, “increase their reputation”

among citizens of more established nations,

“reconcile them to the rest of the world and

procure them its praise.” We can only wonder

if the citizens of the new and old nations who

live and work in Jules de Sibour’s

buildings are so reconciled.

Jefferson was right, in as much as

the legacy of de Sibour’s brilliant Beaux

Arts creations provide a bridge between

our younger country and its European

inheritance. And, while these magnificent

buildings may or may not impress visitors

from other countries, their more lasting

value is that they change the way we

who live here see ourselves, our past and

our possibilities.

|